Kaffenberger in the new World

Join us as we look at the life of the first recorded Kaffenberger immigrant.

Join us as we look at the life of the first recorded Kaffenberger immigrant.

In the mid-1700s, waves of German families left their homeland seeking freedom, land, and opportunity in the American colonies. Among them was Georg Ludwig Kaffenberger (the first recorded Kaffenberger immigrant), born in Stuttgart Germany in 1728, whose journey from the Rhineland to the Shenandoah Valley would lay the foundation and become one of many links for German families across the United States.

The surname Kaffenberger is of German origin, likely a habitational name derived from a place called Kaffenberg or Kaffenburg in the region. The suffix “-berger” means “one who lives by or on a mountain or hill,” while the root “Kaffen” may refer to a topographic or local name now lost to time. As with many German surnames, spelling variations appeared after immigration, including Kassenberger, Kaufenberger, Kaffenburger, Coffinberger, and Coffinberry, reflecting the gradual anglicization of the family name in colonial America.

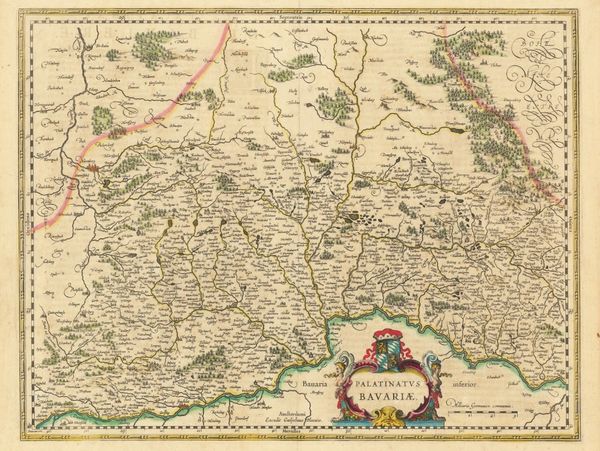

By the early 1700s, the Palatinate region (southwestern Germany) was marked by decades of hardship. The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) and subsequent French invasions devastated towns and farmland, displacing countless families. Heavy taxes, failed harvests, and constant political turmoil made daily survival precarious.

Religious persecution also played a role. While some dissenting sects such as Mennonites and Quakers sought freedom to practice their beliefs, most emigrants were Lutheran or Reformed farmers who left primarily for economic reasons.

The British colony of Pennsylvania, founded by William Penn, became a magnet for these emigrants. Penn’s promises of religious tolerance, affordable land, and self-governance were widely circulated through pamphlets and letters sent back to Europe.

The first permanent German community, Germantown, was founded near Philadelphia in 1683 by settlers from the Krefeld area of the Rhineland. Over the next decades, immigration surged: settlements such as Skippack (1702), Oley (1709), and Conestoga (1709) expanded the German presence. Between 1727 and 1775, an estimated 65,000 Germans arrived in Pennsylvania—many from the Palatinate, Württemberg, Baden, and Swiss-German regions. The peak migration years were 1749–1754, coinciding almost exactly with the period when Georg Ludwig Kaffenberger crossed the Atlantic.

By 1751, German immigrants were firmly woven into colonial life. Nearly a third of all colonists had German roots, and the language filled Pennsylvania’s towns—visible on shop signs, heard in coffeehouses, and printed in newspapers. The strength and vitality of German publishing became one of the cornerstones of this community. Since Gutenberg’s 1440 invention of movable type, Germans had dominated European printing—and brought that craft across the Atlantic. The first Bible printed in America was produced in German by Christopher Saur, a printer in Philadelphia. By the time of the Revolution, nearly every large town had at least one German-language newspaper, sometimes two. These newspapers, almanacs, and broadsides served as the cultural glue that bound scattered German-speaking settlers together across the colonies.

It was into this thriving German-speaking world that Georg arrived on 14 September 1751. His ship, the St. Andrew, sailed from Rotterdam with a stop at Cowes before crossing the Atlantic. The passenger list, later published in Pennsylvania German Pioneers Vol. 1, recorded his name as Georg Ludwig Kaffenberger (also written Kassenberger in another document). Among his fellow passengers was his wife Maria Veronica as well as his father-in-law Valentin Kimmel.

German immigrants were not only industrious settlers but also loyal participants in their new nation’s founding struggles. At the outbreak of the American Revolution, men of German descent formed volunteer militia units in nearly every colony. General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, a veteran of the Prussian army, trained the Continental troops at Valley Forge, introducing drills and discipline that would shape the United States Army for generations. This proud military service would later be reflected within the Kaffenberger family itself, as Georg’s son would go on to serve in the Revolutionary War.

For Georg Ludwig, Philadelphia offered a place that felt both new and familiar. The established German population provided churches, craftsmen’s guilds, and social networks that helped newcomers adapt to life in the colonies while keeping their traditions alive. Drawn by opportunities for land and self-reliance, Georg soon followed a path many families had taken before him, moving south from Pennsylvania into the fertile Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

After arriving in America, Georg and his wife Maria moved south through Pennsylvania’s German settlements into Frederick County, Virginia, part of the fertile Shenandoah Valley. There, in 1763, colonial records first list him under the anglicized name “George Lewis Coffinberry,” marking both his integration into English-speaking society and the beginning of the family’s American identity. That same year, he received a land grant of 282 acres on Opequon Creek from Lord Fairfax’s proprietary office.

The Lord Fairfax grants were part of a vast tract of land held under a semi-feudal system in which settlers paid small annual quitrents in exchange for title and use. These grants encouraged European settlers—especially Germans and Scots-Irish—to populate and cultivate the valley. For George, adopting an English version of his name likely reflected both practicality and allegiance, signaling his willingness to adapt to a British colonial system that prized order, productivity, and loyalty.

Lord Fairfax’s relationships with settlers were largely pragmatic, focused more on productivity than hierarchy, though some still viewed the system as a remnant of feudalism. Fairfax sought industrious tenants to improve the land, and German families like the Kaffenbergers offered precisely that. They cleared forests and built thriving farms, turning the frontier into productive land. Though the quitrent system had critics, it offered settlers the chance to own and pass land to future generations.

As tensions rose between the colonies and Britain, these landholding families—many of them German—found their loyalties divided. The Fairfax estates were tied to the British crown, and the Revolution challenged that system. For some German settlers, military service in the Patriot cause provided both a means to secure their property and to align themselves with the emerging American identity. Within this context, George Lewis Coffinberry Jr. later enlistment in the Revolutionary War can be seen not only as an act of patriotism but also as a commitment to the independence and land the family had worked so hard to claim.

George continued to appear in local records, including tax and tithable lists in both Frederick and later Berkeley County (formed 1772) throughout the 1780s and 1790s. These records trace his steady life as a farmer and community member—proof that he was firmly rooted in Virginia society. The records show a household growing in size and productivity, with land and labor expanding as his family did. These years marked the true settlement of the Coffinberry family, transforming their acreage along Opequon Creek from wilderness into a thriving farmstead.

As the Revolutionary period approached, this rootedness would become central to the Coffinberry legacy. The stability and reputation George built provided a foundation for his children, many of whom would come of age during the Revolution and carry the family’s name into both military and civic life. The farm became more than a homestead—it was the center from which the next generation would take its first steps toward the broader American frontier.

When George and Katrina (Maria Veronica also took an anglicized name) Coffinberry settled on their 282-acre tract along Opequon Creek, they began building not just a farm but a lasting family legacy. Like many Shenandoah Valley settlers, their days revolved around labor and faith. George was a sickle maker by trade, crafting the essential tools that sustained his neighbors’ harvests, and he also served as a Baptist clergyman, ministering to the scattered frontier families of Berkeley County.

The Coffinberry farm was likely modest but busy: log buildings near a creek, fields of corn and grain, and the steady rhythm of planting, harvest, and forge work through the seasons. Katrina managed a large household and bore at least eight children who survived to adulthood.

Their home likely doubled as both workshop and meeting place—a center of labor, faith, and community. Visitors would have found a household where craftsmanship met devotion, the forge and pulpit standing side by side. Through their work, their worship, and their growing family, George and Katrina helped root the German-American presence in Virginia soil, setting in motion a legacy that their children would carry into a rapidly changing America.

Their family grew alongside the new nation. The children—Mary, Elizabeth, Nancy, Frances, Sarah, Catherine, Jacob, and George Jr.—each carried a part of their parents’ pioneering spirit. Some married into nearby families, while others moved further west into Maryland, Ohio, and Indiana, following the same instinct for independence that brought their parents across the Atlantic.

Born in 1760 near Martinsburg, Virginia, George Lewis Coffinberry Jr. grew up on the family’s Opequon Creek farm. When the Revolutionary War began, sixteen-year-old George enlisted from Berkeley County in Captain Culbert Anderson’s company and served in the Carolinas under General Nathanael Greene. Like many sons of immigrant settlers, his service tied the family’s story to the founding of the nation. While George Sr. didn't enlist, the Daughters of the American Revolution record his support furnishing supplies for the colonial army.

After the war, George Jr. returned home and in 1786 married Elizabeth “Klein” Little in Martinsburg. Ambitious and educated, he soon entered public life—first studying law and then being elected to the Virginia Legislature around 1790. Around this time, he petitioned to change his surname from Kaufenbaerger to Coffinberry—completing the family’s transition into its American identity.

In the years that followed, George Jr. embodied the restless energy of a new nation pushing westward. He led his young family across the mountains, blazing the first wagon road between Wheeling and Chillicothe, Ohio. There he helped establish new settlements, published Ohio’s first newspaper, The Olive Branch, and later built and operated The North American Hotel in Mansfield. His ventures as a pioneer, lawyer, publisher, and politician reflected both enterprise and civic spirit, while his later years as a Presbyterian elder showed a life rooted in faith and service.

George Jr. and Elizabeth Coffinberry raised thirteen children who spread throughout Ohio and the Midwest, carrying the family’s influence into education, public service, and industry. When George died in 1851 at the age of ninety-one, his life traced the full arc of America’s first century—from colonial frontier to the settled towns of the West. Through him, the Coffinberry legacy of craftsmanship, faith, and perseverance found its enduring place in the American story.

Family records and George’s 1812 will reveal a life built on fairness and faith: he left equal shares of his estate to all eight of his children, ensuring that each carried forward a portion of the land and labor that had defined his life.

The story of Georg Ludwig Kaffenberger and his son George Lewis Coffinberry Jr. reflects the journey of countless immigrant families who helped shape early America. From a Rhineland village to Philadelphia’s busy streets, from a Virginia clearing to Ohio’s prairies—their lives traced the transformation of a continent.

Through labor, faith, and vision, the Coffinberry family embodied the persistence that defined the new nation—from Georg’s forge and pulpit to his son’s pen and pioneering drive. . Their descendants carried those same values westward, turning the family’s story into part of the larger American narrative—one rooted in courage, devotion, and the enduring promise of opportunity.

Today, the name Coffinberry still echoes in the regions they helped settle, a reminder of how one family’s determination became woven into the fabric of the United States.

Copyright © 2025 Kaffenberger - All Rights Reserved.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.